January 18, 1943

THAT DAY..................................................the Germans entered the Warsaw Ghetto to continue the deportation, and they expected no resistance, but Jews refused to assemble for the transport, and an armed resistance broke out.

In 1939, German authorities began to concentrate Poland's population of over three million Jews into a number of extremely crowded ghettos located in large Polish cities. The largest of these, the Warsaw Ghetto, collected approximately 300,000–400,000 people into a densely packed, 3.3 km2 central area of Warsaw. Thousands of Jews were killed by rampant disease and starvation under SS-und-Polizeiführer Odilo Globocnik and SS-Standartenführer Ludwig Hahn, even before the mass deportations from the ghetto to the Treblinka extermination camp began.

In January 1943 there were only 60,000 Jews left in the Warsaw Ghetto. They were what remained of the approximately 440,000 Jews who had been confined there. One-fifth had died of disease and starvation during the past two years, and the previous summer some 265,000 had been deported to the Treblinka extermination camp, and over 30,000 to other camps.

With Czerniakow dead (the head of the Jewish Council, who had committed suicide rather than comply with German demands to provide census information about the ghetto) and in wake of the deportations, a new de facto leadership emerged in the ghetto – the Jewish Fighting Organization, the ZOB, headed by Mordecai Anielewicz. The ZOB was a coalition primarily of various Zionist youth movements and the Jewish socialist Bund. Alongside it there was a smaller armed underground group,

on January 18, 1943, seventy years ago, German forces entered the ghetto to round up Jews for transport. They planned to take about 8,000 people, but the ghetto population believed the final destruction of the ghetto was at hand. To the great surprise of the German forces, they met armed resistance.

Hundreds of people in the Warsaw Ghetto were ready to fight, adults and children, sparsely armed with handguns, gasoline bottles, and a few other weapons that had been smuggled into the ghetto by resistance fighters. Most of the Jewish fighters did not view their actions as an effective measure by which to save themselves, but rather as a battle for the honour of the Jewish people, and a protest against the world's sile

A group of Hashomer Hatsair members, led by Anielewicz and armed with pistols they had received from the Polish Home Army (AK), intercepted a column of Jews being led by a German force and fired upon the solders. In a nose-to-nose battle, most of the underground contingent was killed, but Anielewicz managed to overpower the soldier with whom he was struggling and he escaped unharmed. The news of the clash spread quickly to other cells of the underground and they too began to resist. Yitzhak Zuckerman, with a party from the Dror youth movement, lay in wait for the German force on Zamenhof Street, and when they approached fired a volley at them.

During four days the Germans tried to round up Jews and were met by armed resistance. The ghetto inhabitants went through a swift change. With the news of the first incident of fighting they stopped responding to the Germans’ calls that they gather in the Umschlagplatz. They began devising hiding places, and the Germans had to enter many buildings and ruthlessly pull out Jews. Many were killed in their homes when they refused to be taken. On the fourth day, having only managed to seize between five and six thousand Jews, the Germans withdrew from the ghetto. The remaining inhabitants believed that the armed resistance combined with the difficulties in finding Jews in hiding, had led to the end of the Aktion. As a result, over the next months the armed undergrounds sought to strengthen themselves and the vast majority of ghetto residents zealously built more and better bunkers in which to hide.

Dr. Robert Rozett, a Senior Historian in the International Institute for Holocaust Research said « The January 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising teaches us a great deal about the human spirit, about resilience, and about courage. It demonstrates that the very act of resistance against oppression can inspire further resistance »

On April 1943 19 April 1943, on the eve of Passover, the police and SS auxiliary forces entered the ghetto. They were planning to complete the deportation action within three days, but were ambushed by Jewish insurgents firing and tossing Molotov cocktails and hand grenades from alleyways, sewers, and windows. The Germans suffered 59 casualties and their advance bogged down. Two of their combat vehicles (an armed conversion of a French-made Lorraine 37L light armored vehicle and an armored car) were set on fire by the insurgents' petrol bombs.

Following von Sammern-Frankenegg's failure to contain the revolt, he lost his post as the SS and police commander of Warsaw. He was replaced by SS-Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop, who rejected von Sammern-Frankenegg's proposal to call in bomber aircraft from Kraków. He led a better-organized and reinforced ground attack.

The longest-lasting defense of a position took place around the ŻZW stronghold at Muranowski Square, where the ŻZW chief leader, Dawid Moryc Apfelbaum, was killed in combat. On the afternoon of 19 April, a symbolic event took place when two boys climbed up on the roof of a building on the square and raised two flags, the red-and-white Polish flag and the blue-and-white banner of the ŻZW. These flags remained there, highly visible from the Warsaw streets, for four days.

While the battle continued inside the ghetto, Polish resistance groups AK and GL engaged the Germans between 19 and 23 April at six different locations outside the ghetto walls, firing at German sentries and positions.

The suppression of the uprising officially ended on 16 May 1943, when Stroop personally pushed a detonator button to demolish the Great Synagogue of Warsaw.

The SS and police deported approximately 42,000 Warsaw ghetto survivors who were captured during the uprising. These people were sent to the forced-labor camps at Poniatowa and Trawniki, and to the Lublin/Majdanek concentration camp. Most of them would be murdered at these camps in November 1943 in a two-day shooting operation known as Operation Harvest Festival (Erntefest).

At least 7,000 Jews died fighting or in hiding in the ghetto. Approximately 7,000 Jews were captured by the SS and police at the end of the fighting. These Jews were deported to the Treblinka killing center where they were murdered.

For months after the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, individual Jews continued to hide in the ruins of the ghetto. On occasion, they attacked German police officials on patrol. After the ghetto was liquidated, perhaps as many as 20,000 Warsaw Jews continued to live in hiding on the so-called Aryan side of Warsaw.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943 took place over a year before the Warsaw uprising of 1944. The ghetto had been totally destroyed by the time of the general uprising in the city, which was part of the Operation Tempest, a nationwide insurrection plan. During the Warsaw Uprising, the Polish Home Army's Battalion Zośka was able to rescue 380 Jewish prisoners (mostly foreign) held in the concentration camp "Gęsiówka" set up by the Germans in an area adjacent to the ruins of former ghetto. These prisoners had been brought from Auschwitz and forced to clear the remains of the ghetto. A few small groups of ghetto residents also managed to survive in the undetected "bunkers" and to eventually reach the "Aryan side.

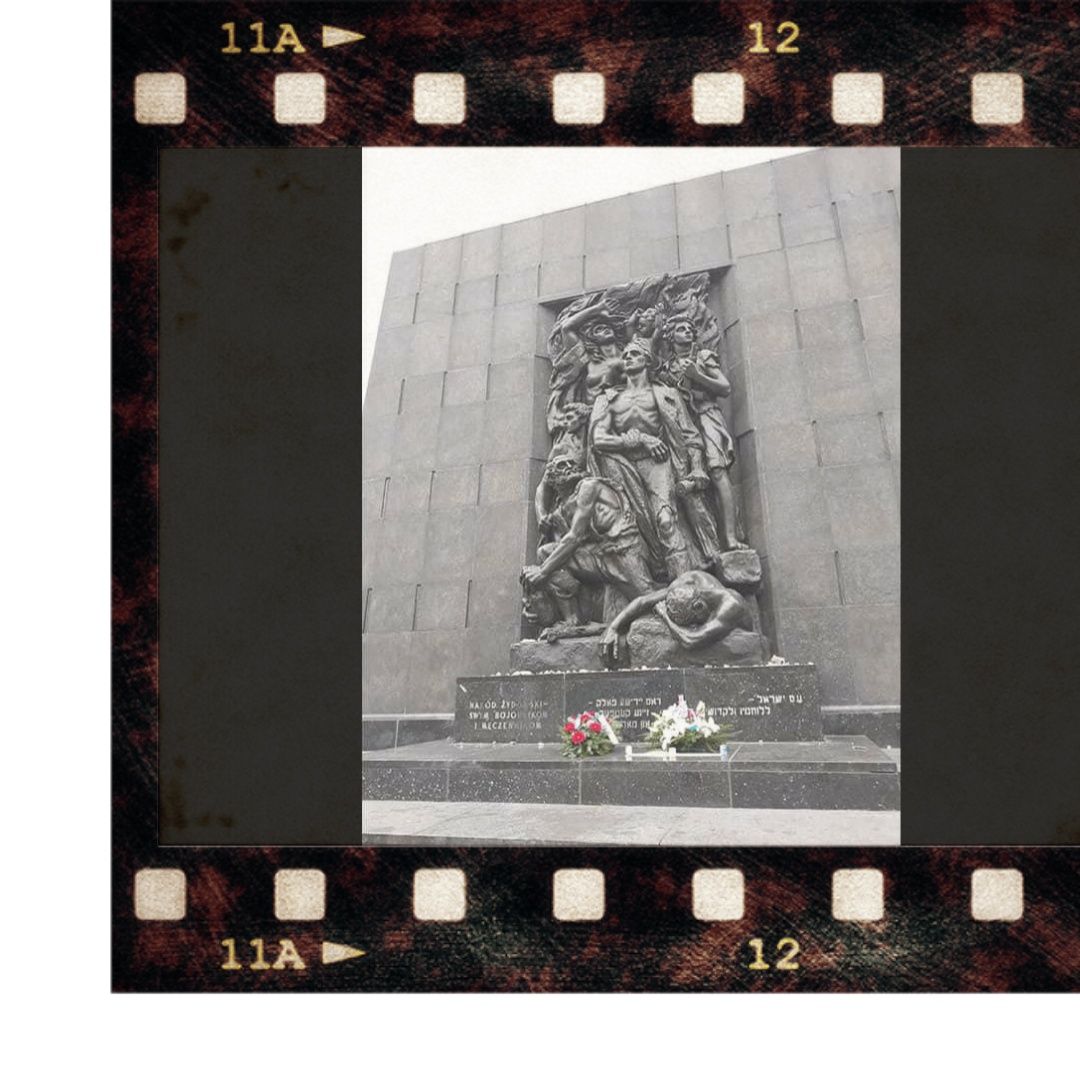

The Warsaw ghetto uprising was the largest and, symbolically, most important Jewish uprising during World War II. It was also the first urban uprising in German-occupied Europe. The Jewish resistance in Warsaw inspired uprisings in other ghettos such as in Bialystok and Minsk.ool

In 1968, the 25th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Zuckerman was asked what military lessons could be learned from the uprising. He replied:

I don't think there's any real need to analyze the Uprising in military terms. This was a war of less than a thousand people against a mighty army and no one doubted how it was likely to turn out. This isn't a subject for study in military school. (...) If there's a school to study the human spirit, there it should be a major subject. The important things were inherent in the force shown by Jewish youth after years of degradation, to rise up against their destroyers, and determine what death they would choose: Treblinka or Uprising

To know more about the subject:

"Europe | Warsaw Jews mark uprising". BBC News. 20 April 2003. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

Voices From the Inferno: Holocaust Survivors Describe the Last Months in the Warsaw Ghetto – January 1943: In the Bunkers During the Uprising, An online exhibition by Yad Vashem

Stefan Korbonski The Polish Underground State: A Guide to the Underground, 1939–1945 Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

"The Last Letter from the Bund Representative with the Polish National Council in Exile". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

Stroop (1943), pp. 77–78.

Moshe Arens. "Flags over the Warsaw Ghetto." Gefen Publishing House, 2011.

"The Warsaw Ghetto: The Stroop Report – "The Warsaw Ghetto Is No More" (May 1943)". Jewish Virtual Library.

Israel Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 1939–1945: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt, Indiana University Press, 1982 (p.393–394)

Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, Third Edition, Yale University Press, 2003

Regina Domańska: Pawiak... op.cit, p. 417.[full citation needed]

Voices From the Inferno: Holocaust Survivors Describe the Last Months in the Warsaw Ghetto – Clearing the Remains of the Ghetto. An online exhibition by Yad Vashem

Voices From the Inferno: After the Uprising: Life Among the Ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto. An online exhibition by Yad Vashem

Samuel Krakowski War of the Doomed – Jewish Armed Resistance in Poland, 1942–1944 ISBN 0-8419-0851-6, pp. 213–14, Holmes & Meier Publishers 1984

Azoulay, Yuval. "IDF Chief, in Warsaw: Israel, its army are answer to Holocaust", Haaretz, 29 April 2008.

A. Polonsky, (2012), The Jews in Poland and Russia, Volume III, 1914 to 2008, p. 537

Joshua D. Zimmerman (5 June 2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

Strzembosz (1978), page 103.[full citation needed]

Witkowski (1984).

Joshua D. Zimmerman (5 June 2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

Joshua D. Zimmerman (5 June 2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

Joshua D. Zimmerman (5 June 2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

Stefan Korbonski, "The Polish Underground State: A Guide to the Underground, 1939–1945", pages 120–139, Excerpts Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Strzembosz (1983), p. 283.

"Statement by Stroop to Investigators About His Actions in the Warsaw Ghetto". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. 24 February 1946. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

Moczarski (1984), p. 103.

Stroop Report 19 April 1943 at JPFO Site.

Stroop (1943), p. 7.

Hal Erickson (2008). "Border-Street – Trailer – Cast – Showtimes". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2012.(subscription required)

"Jack Eisner, 77, Holocaust Chronicler, Dies". The New York Times. 30 August 2003.